Looking at the rib cage can help give information about how you breathe, how you manage pressure, and how you engage your core. Does your lower rib cage expand when you take a breath? The infrasternal angle at the lower ribs can also tell us if your external obliques or your internal obliques are working harder than other core muscles. This angle, which is formed at the bottom of the sternum and the lower ribs, can give us clues about how you manage pressure in the abdominal cavity and how that might impact your pelvic floor and lower back.

Let’s talk about anatomy for a bit. There are quite a few muscles that attach to the lower ribs including the latissimus dorsi, external obliques, internal obliques, transverse abdominis, quadratus lumborum, rectus abdominus, serratus anterior, serratus posterior inferior and the diaphragm. These muscles are not only attaching around the lower ribs, but they are also attaching to each other through our fascial network. These structures connect the upper body to the lower body and help transmit energy and movement from one area of the body to another. Coordinated effort between the breath and the fascia/muscles provides us with good pressure management in the trunk along with greater ease of movement.

As you inhale, the diaphragm flattens and broadens. As you exhale, it rises back up to its resting, domed position. One of its functions is that it works together with the pelvic floor to help you stabilize your spine and abdominal cavity during daily activities. Some of these muscles reflexively engage when you initiate a movement with your arm or when get ready to move your body. Research has shown that when people have back pain, this protective engagement of core muscles is delayed or absent when you initiate a movement. This delay causes more difficulty in spinal stabilization during activity.

The external obliques are along the side body between the ribs and pelvis. They pull the ribs down and in causing a narrow position at the front of the lower ribs. The internal obliques are the next layer under the external obliques and they run in the opposite direction between the ribs and pelvis. They pull the lower front ribs down and out causing a wider position at the front of the lower ribs.

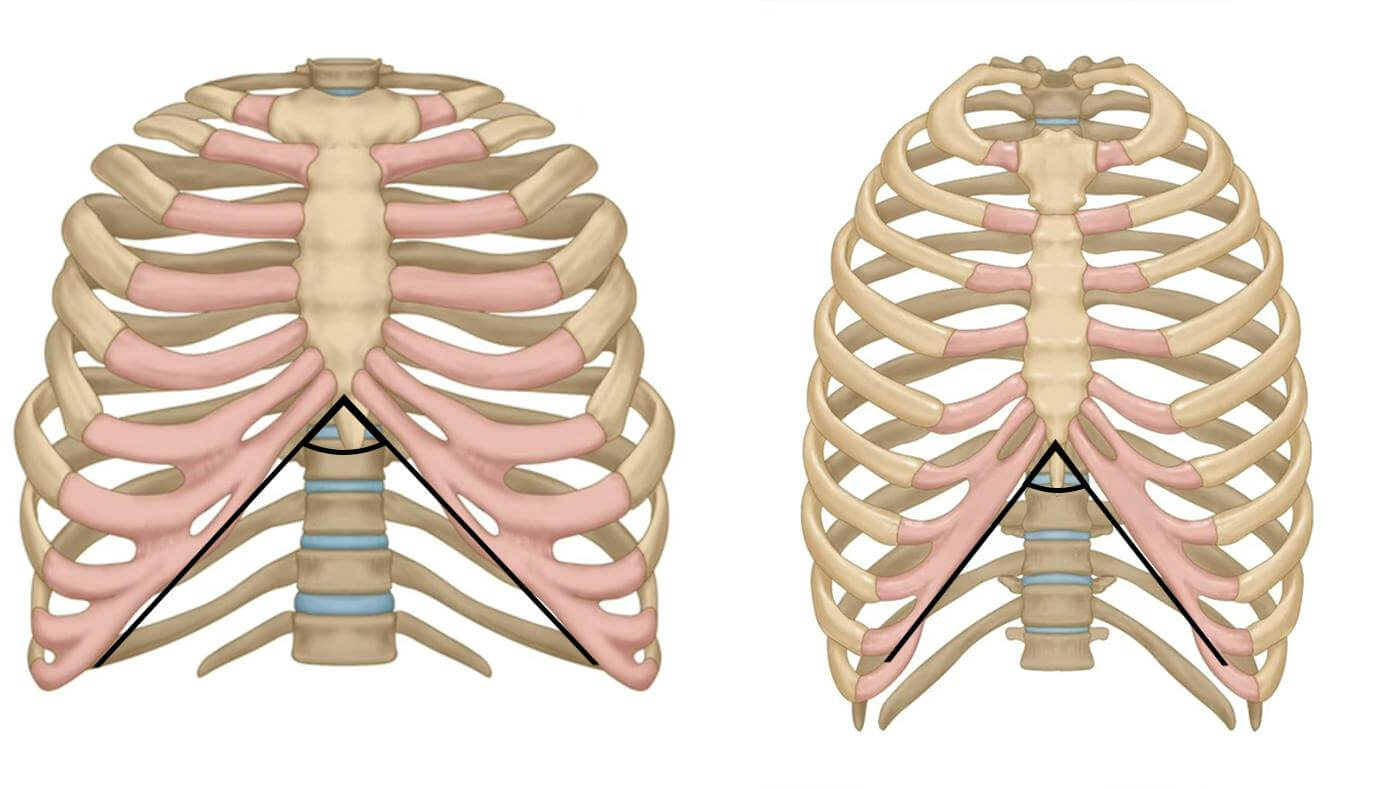

The angle of the ribs can give you clues about how much pressure you might place down onto the pelvic floor when you sneeze, cough, laugh, or lift heavy objects. This angle also can give you clues about how you use your oblique muscles. In the picture on the left, you can see that the ribs are wide, and, on the right, the rib angle is more narrow. Look at your own body noticing the angle you see or feel. Typically, we try to see if it is around 90 degrees, or a right angle. If it is less than 90 degrees, it is more narrow, and greater than 110 degrees is considered a wide angle.

photo courtesy of Rosaperformanceandwellness.com

If you have a wide angle, what does that mean?

It can mean that you are more internal oblique dominant. The internal obliques(IO) are pulling your ribs apart. If you have a diastasis recti(common during pregnancy) then being more IO dominant can possibly widen the diastasis. It can mean that you are more biased toward internally rotated positions. It can also mean that when you breathe, your rib cage widens out more side to side and you may be more of a belly breather. You may naturally tend toward internal rotation in the hips, pronation in the feet and a more arched lower back.

If you have a narrow angle, what does that mean?

It can mean that you are more external oblique dominant. The external obliques(EO) are pulling your lower ribs together. It can mean that the rib cage is biased toward a more externally rotated position. When you breathe, your rib cage may expand more front to back rather than side to side. Your feet may be more supinated. You may also have a flatter appearance in your lower back.

Why does this matter?

Optimal rib cage mobility during breathing patterns occurs in a 360 degree pattern meaning that that rib cage expands along the front, sides, and the back. This provides for the best movement of the diaphragm and the pelvic floor. When there is synchronization between the diaphragm and pelvic floor, our body has the best chance of using the core during functional movements while maintaining optimal intra-abdominal pressure.

When intra-abdominal pressure rises, there is increased pressure on the spine that helps to stabilize the spine. When there is an imbalance between pressure produced and muscle strength, we can have issues with hernias, pelvic organ prolapse, incontinence, and spine/disc problems.

If we are more dominant with the internal obliques or the external obliques, it may disrupt our ability to engage the transverse abdominis which is our body’s own natural corset. I have previous posts on the transverse abdominis, external obliques and internal obliques and I’ll link to those at the bottom of this post if you want to read more about these muscles!

Wider angles cause a more inhaled(descended) state of the diaphragm, so you’d want to work on your exhalations to help the diaphragm move up into its domed position. This descended position makes it difficult to inhale deeply because the diaphragm cannot descend further. Narrow angles cause a more exhaled(domed) state of the diaphragm, so you’d want to ensure you get lower rib cage movement with inhalation to encourage diaphragm flattening and widening. If the diaphragm cannot descend well, the pelvic floor cannot descend well. This leads to increased tension, stiffness, and tightness in these muscles.

The first place to start is with the breath whether you have a narrow or a wide rib cage. Aiming for breathing into a full 360 degree arc along the lower rib cage is a good place to begin. A good place to begin is laying on your back with your hips and knees bent at a 90 degree position of the hips and the knees. Set up your phone or tablet and video your body from the side to observe how you breathe. You can also use your hands by placing them on various places on your body and feel how you breathe.

Things to notice:

Belly rise

Front rib rise

Side rib expansion

Lower back arching

Lower back rib cage expansion

Chest rise

Neck muscle tension

Ideally, you would feel the belly, ribs and chest all rise evenly. You would not feel the lower back arch on the inhale. You would not see a “sucking in” under the front ribs with your inhale. You would not see the lower belly pooch outward on your exhale. You would not feel your neck muscles tense up on the inhale. You would not see high chest rising on inhale. You would not see the belly rising more than the rib cage.

I’d love to know what you notice when you breathe! Where does your body move when you breathe? Do you have a wide or narrow angle? Would you like to know more about how to exercise in order to create more balance around the rib cage, abdomen and hips?

Take good care,

Sharon

The internal obliques

The internal obliques starts at the front of the pelvis as well the the thoracolumbar fascia(along the lower back area) and inserts into the lower 3 ribs on each side and the middle of the abdomen along the front midline. Place your hands on the sides of your trunk and act as if you are putting your hands into your back …

The external obliques

The external obliques start along the 5th-12th ribs and insert into the top ridge of the pelvis. Act as if you are reaching your hands into your front pockets on your pants. This is the orientation of the external oblique muscle fibers. They help move the rib cage and upper trunk over the pelvis. There’s one on each side…

The transverse abdominis

Being the deepest core muscle on the front of the abdomen, the transverse abdominis originates in the thick fascia(connective tissue) in the lower back and wraps around the trunk and inserts into the front of the lower ribs, the pelvis, pubic bone and along the midline of the front body called the linea alba. This muscle is y…